I know it’s Christmas Eve but you’ll have to forgive me for going deep on the notion of science and moral responsibility.

The Biden administration has reversed a decades-old decision to revoke the security clearance of Robert Oppenheimer, the physicist called the father of the atomic bomb for his leading role in World War II’s Manhattan Project.

In stripping Oppenheimer of his clearance, the Atomic Energy Commission did not allege that he had revealed or mishandled classified information, nor was his loyalty to the country questioned, according to Granholm’s order. The commission, however, concluded there were “fundamental defects” in his character.

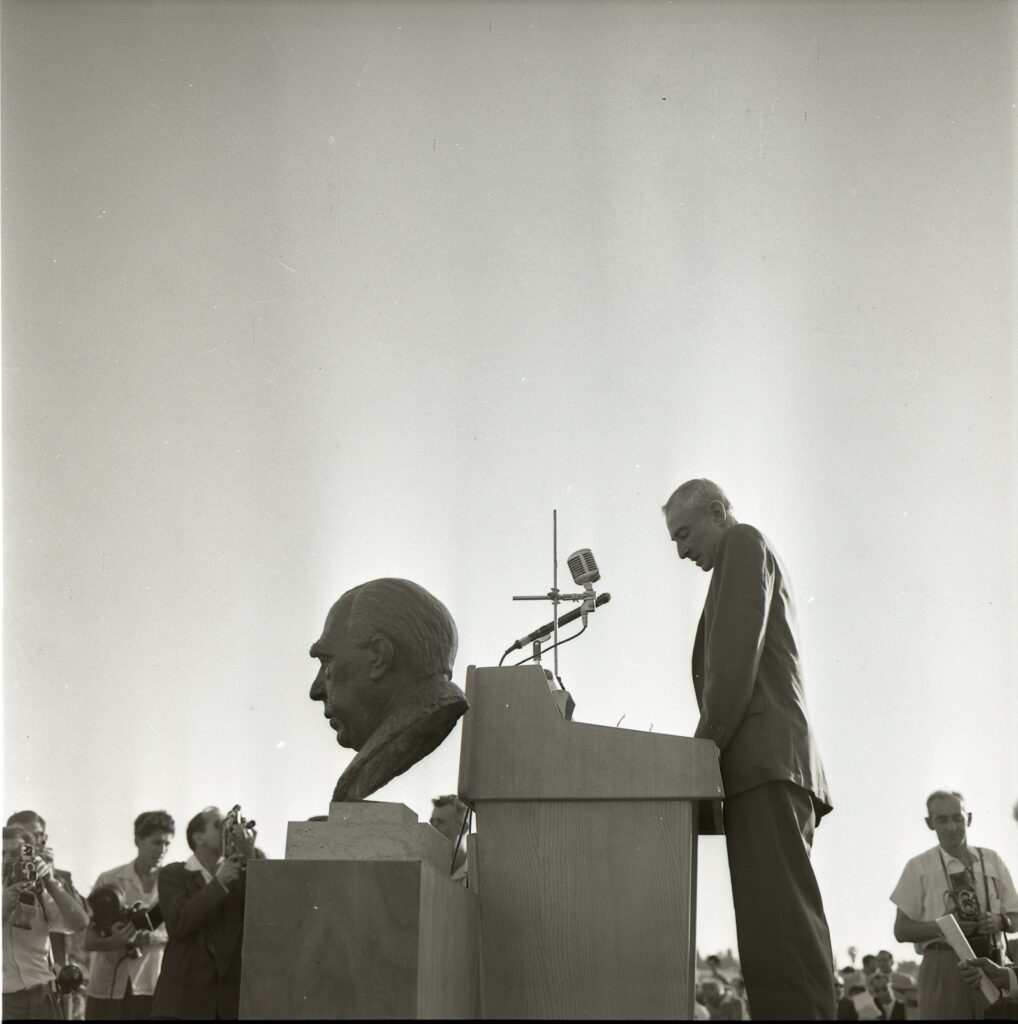

Oppenheimer wrongly stripped of security clearance, US says

In hindsight, it’s hard to divorce the revocation of Oppenheimer’s security clearance from his complicated views on his role as the “father of the atomic bomb.” Especially when you look at how that revocation has been used in the past: to punish those who spoke out against the use of the power of the state to bring violence.

It’s tempting to see the revocation of Oppenheimer’s clearance as punishment for speaking out, and the restoration as an endorsement of his views.

In this case, it’s too simple a formulation. Oppenheimer never apologized for his part in the creation of man’s most horrific weapon, nor did he regret its use in the war. He did, however, take responsibility for all it unleashed and the death it wrought. But he also saw scientific knowledge as an end worth pursuing, no matter the costs.

It’s a complicated legacy and worth revisiting.

Oppenheimer’s most famous quote comes from a 1965 documentary about the atomic bomb. In it, he intones a line from the Bhagavad Gita, a Hindu book: “Now I am become Death, the destroyer of worlds.”

This BBVA OpenMind piece delves into the quote’s original context within Gita and within Oppenheimer’s supposed pacifism:

Vishnu wants to convince Prince Arjuna that he must go to war, something that he refuses because it would involve killing his own relatives and friends. But Vishnu convinces him that he cannot shun that duty greater than he—it is his obligation, and it is not in his hand to choose. In the end, Arjuna goes to war.

Oppenheimer, Hijiya concluded, did not see himself as Vishnu. He did not arrogate the role of a god. He was Arjuna, the prince destined to fulfill that unavoidable duty, a terrible test for a pacifist who had always been one, both before and after the bomb.

Alex Wellerstein at the Nuclear Security Blog (linked in the article above) goes deeper on the context of Gita and speculates on Oppenheimer’s place in the atomic age:

Oppenheimer is not Krishna/Vishnu, not the terrible god, not the “destroyer of worlds” — he is Arjuna, the human prince! He is the one who didn’t really want to kill his brothers, his fellow people. But he has been enjoined to battle by something bigger than himself — physics, fission, the atomic bomb, World War II, what have you — and only at the moment when it truly reveals its nature, the Trinity test, does he fully see why he, a man who hates war, is compelled to battle. It is the bomb that is here for destruction. Oppenheimer is merely the man who is witnessing it.

What I find strange and somewhat abhorrent in Oppenheimer is his laissez-faire point of view on what comes next. Personally, I’ve always been more of a Malcolmist in my views.

At the risk of seeming like I’m putting words in Oppenheimer’s mouth, here he is in his farewell speech to Los Alamos in 1945 – the year the bomb dropped:

If you are a scientist you cannot stop such a thing. If you are a scientist you believe that it is good to find out how the world works; that it is good to find out what the realities are; that it is good to turn over to mankind at large the greatest possible power to control the world and to deal with it according to its lights and its values.

Later in the speech, Oppenheimer addresses the common occurrence of technology’s creation moving faster than our ability to reckon with it:

There was a period immediately after the first use of the bomb when it seemed most natural that a clear statement of policy, and the initial steps of implementing it, should have been made; and it would be wrong for me not to admit that something may have been lost, and that there may be tragedy in that loss. But I think the plain fact is that in the actual world, and with the actual people in it, it has taken time, and it may take longer, to understand what this is all about.

We have not yet solved for our inability to reckon with the uses of new technology before its consequences are unleashed. This is true whether we are speaking of drugs, social media, or crypto. Some tools contain inherent harm, some are merely harmful when abused.

Oppenheimer wrote this piece for The Atlantic in 1949, four years after he wrote the above, and five years before his security clearance was stripped. It’s a beautiful piece of philosophy and a meditation on the use of the unimaginable power of the state to create or destroy. In it, Oppenheimer somewhat fulfills his call for the consideration of this technology after the fact and begins to reckon with it:

In foreign affairs, we are not unfamiliar with either the use or the need of power. Yet we are stubbornly distrustful of it. We seem to know, and seem to come back again and again to this knowledge, that the purposes of this country in the field of foreign policy cannot in any real or enduring way be achieved by coercion.

[SNIP]

It is true that one may hear arguments that the mere existence of our power, quite apart from its exercise, may turn the world to the ways of openness and of peace. But we have today no clear, no formulated, no in some measure credible account of how this may come about. We have chosen to read, and perhaps we have correctly read, our past as a lesson that a policy of weakness has failed us. But we have not read the future as an intelligible lesson that a policy of strength can save us.

Back to 1965 and the Gita. In another clip, Oppenheimer suggests the hope that the mere existence of atomic bomb would mean it would not need to be used and would bring an end to the war.

Oppenheimer and the scientists he worked with may indeed be Arjuna. But in their conversation with Vishnu, with technology’s most terrible form come to life, how could they look upon it and not reckon more with its use before unleashing it on the world?

There are no simple answers here. But if science is separated from philosophy then we are at the mercy of its effects. That’s Oppenheimer’s legacy.